Scrum is intended as a simple, yet sufficient framework for complex product delivery. Scrum is not a one-size-fits-all solution, a silver bullet or a complete methodology. Instead, Scrum provides the minimal boundaries within which teams can self-organize to solve a complex problem using an empirical approach. This simplicity is its greatest strength, but also the source of many misinterpretations and myths surrounding Scrum. In this series of posts we — your ‘mythbusters’ Christiaan Verwijs & Barry Overeem — will address the most common myths and misunderstandings. PS: The great visuals are by Thea Schukken. Check out the previous episodes here (1, 2, 3, 4 , 5, 6, 7, 8).

Myth: Story Points are Required in Scrum

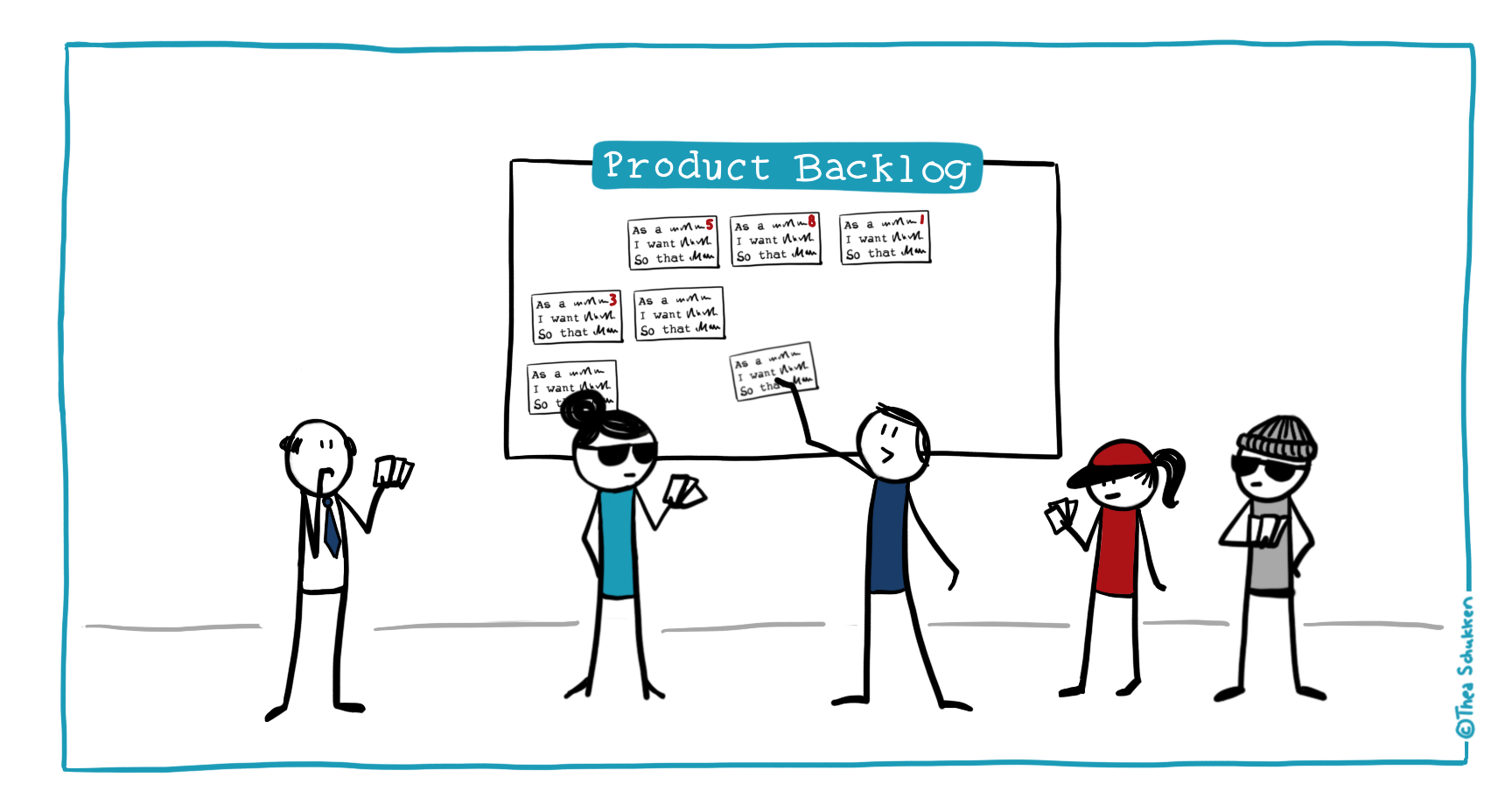

Today we address the idea that work on the Product Backlog must be estimated in Story Points. The majority of the teams that we work with do this, and there really is nothing inherently wrong with it. The myth begins where people misunderstand the purpose of estimation in Scrum and Story Points become an end in themselves.

For those unfamiliar with Story Points; teams that use this technique estimate effort with relative estimates instead of time-based estimates (e.g. hours, days). This is usually done with a simplified version of the Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, etc). The numbers have no meaning in themselves, but only in relation to other items. So an item of 5 points takes roughly twice as much effort from the team as an item of 3 points, and so on. Several methods exist to estimate Story Points, including Planning Poker and Magic Estimation.

Although the use of Story Points is the most widely spread technique, we could easily generalize this post to include estimates in hours, ideal days or t-shirt sizes for that matter.

Busting the Myth

As with previous posts, let’s start with what the Scrum Guide says on estimation. Although it states that “work may be of varying size, or estimated effort”, it does not prescribe how this estimation should be done. Although Scrum Teams should apply some sort of ‘estimation’, there is no mention of Story Points, hours, ideal days, gut feeling, t-shirt sizes or any other unit for that matter. The Scrum Guide does remind us to use an approach that respects the complexity of software development and to not let estimation replace the importance of empiricism itself.

So we can easily bust this myth with the Scrum Guide alone. But a more thorough explanation helps to better understand why.

The Purpose of Estimation in Scrum

In plan-based approaches, estimates are used to arrive at budgets and to determine delivery dates. Supposing that the estimates are accurate, they provide us with a means to manage (financial) risks of spending either too much money or spending money on the wrong things.

The primary purpose of estimates in Scrum is to give Development Teams a rough sense of the amount of work they can pull into a Sprint. This requires a conversation between members; ‘What is involved?’, ‘How should it work?’ and ‘What work is needed?’. Although the Development Team commits to achieving the Sprint Goal, they do not commit to completing all this work within the Sprint. As even within a single Sprint, unexpected problems and insights are likely to emerge.

This underscores that the role of estimates is quite different in Scrum — and something that people coming from a plan-based perspective often struggle with. Scrum is built on the observation that software development is a very complex endeavor, making it impossible to arrive at accurate estimates. In complex environments, what will happen in the (near) future is largely unknown. New and better insights will emerge and unexpected problems surface as we work together to discover both the problem and the (most suitable) solution. Instead of relying on estimates to forecast and control what happens in the future, we should use the empirical process of Scrum to capitalize on change rather than control against it. As the Scrum Guide observes: “Only what has already happened may be used for forward-looking decision-making”.

“Use the empirical process of Scrum to capitalize on change rather than control against it.”

This provides us with four important insights with regard to estimates:

- Accurate estimates are impossible, as even the most thorough, detailed technique can’t cover all scenarios, potential issues, insights that may emerge and external factors that influence our work. Let alone entirely unexpected events (called ‘Black Swans’);

- An estimate can’t be a guarantee. “An estimate is simply a prediction based on known information and input at a given point in time” — Ilan Goldstein;

- The time we spend on estimation is a form of waste. Estimates are inaccurate at best and the work we are estimating is likely to change dramatically as our understanding changes over time (or may even be dropped from the Product Backlog);

- The estimates themselves are the result of a necessary conversation within the Development Team to arrive at a shared understanding.

Instead of spending a lot of time and effort on estimation, we’re better off spending that time on building valuable software and using the empirical process of Scrum to learn. The question now becomes; what method of estimation is ‘just-good-enough’ to help Development Teams select a do-able amount of work for a Sprint and getting a sense of what is needed, while requiring as little time and effort as possible.

Time-based estimates — hours, ideal days — are one option. A major disadvantage is that they tend to uphold the illusion of accuracy and predictability, and are often interpreted as such. Another disadvantage is that their illusion of accuracy often drives teams into ‘analysis paralysis’, where all details need to be discussed in-depth in order to arrive at a detailed estimate.

“Time-based estimates uphold the illusion of accuracy and predictability.”

This is why the use of relative estimation, in particular ‘Story Points’, was popularized by Extreme Programming. Relative estimates are not based on units of time, and avoid all pretense of detail and accuracy. But they can provide Development Teams with a guide on the amount of work they may be able to complete within a Sprint. Take this example:

Suppose a Development Team has been working together for 20 Sprints. The empirical process of Scrum has taught them that they can complete — on average — 35 points of work (their so-called velocity). Based on what has already happened, the Development Team has a rough sense of the amount of the work (about 35 Story Points) that they can pull into their next Sprint. Furthermore, this empirical data (~35 Story Points) can be used by the Product Owner to create a rough forecast for specific features or releases. If a Development Team can take on 35 Story Points of work per Sprint, and there are 350 Story Points of work on the Product Backlog, it would not be unreasonable to anticipate another 10 Sprints to complete the Product Backlog in its current state.

So Story Points are a lightweight approach to get a rough idea of how much work can be completed in a Sprint. It remains a rough indicator, however. But at least it is based on what has already happened and not on what we hope will happen. Estimation in hours or ideal days is certainly still an option, but teams need to be aware of their disadvantages.

Why Estimate At All?

If estimation is largely waste, it makes sense to ask: “Why even bother?”. This point is raised by the #NoEstimates-movement. They encourage to build small chunks of work incrementally, leading as rapidly as possible to a desired shippable product, without spending endless hours on trying to predict the future. We don’t want to go into a #NoEstimate debate here, but we do want to offer some alternatives to estimating individual items:

- Use the number of items per Sprint as a guide to select a doable amount of work for a Sprint. For example, a Development Team may know from experience that they can complete between 6 and 8 items per Sprint. This requires that items are broken down to about equal size;

- Use size buckets as a guide, where the Development Team classifies items in terms of size (e.g. large, medium, small). It may know from experience that it can complete 1 large item, 2–3 medium-sized items, and 4–6 small-sized items;

- Simply use the combined gut feeling of the Development Team to determine if enough work was selected for the Sprint;

Although some of these approaches may complicate forecasting based on historical results, they are viable alternatives that fit well within the Scrum Framework and its purpose for estimation.

Probably the most important reason why we feel that estimation is useful is that it helps to focus the conversation within a Development Team on what is needed for a particular item. Having to arrive at some kind of estimate, often helps to trigger the right kind of discussions: “What is needed?”, “Can we find a simpler solution?”, “Have we considered X?”. Estimation is not so much about the estimates, but about the discussions that it triggers. It’s about having a conversation — ideally with the actual customer — and creating a shared understanding.

“Estimating is often helpful, estimates are often not.” — Esther Derby

Tips

- Whatever you do in terms of estimation, make sure to do it with the entire Development Team. The process of estimation is not solely about the resulting number, but perhaps even more about the communication that takes place within the team to arrive at a shared understanding of the work involved. By pooling your expertise, creativity, and experience, you are more likely to identify potential issues or oversights;

- Some teams want to stick to hour-based estimates because it feels ‘more real’ or easier to estimate for them. One approach is to create time buckets with increasing intervals (e.g. 1 hour, 2–3 hours, 3–5 hours, 5–8 hours). This communicates more clearly the growing uncertainty as a result of a higher estimate;

- Explore different techniques and determine what works best for your Development Team, and requires as little effort and time as possible;

- Don’t ask the customer what software you need to build. Instead, figure out what problem the customer wants to solve and determine how you’ll know when it is solved;

- With software development “I don’t know” is a valid answer to questions like “how much will it cost” or “how long will it take”.

Closing

In this post, we busted the myth that Scrum requires work to be estimated in Story Points. Although it is a useful technique, and used by many Scrum Teams, it is by no means the only technique. We used this post to describe some alternatives and to explain why Story Points became prevalent. By doing so, we also explained how estimation fulfils a different role in Scrum than compared to plan-based approaches.

Above all, remember the quote by Esther Derby: “Estimating is often helpful, estimates are often not.” The more complex the activity at hand, the more important communication and collaboration gets.

“Respect the complexity of software development, and don’t let estimation replace the importance of empiricism itself.”

What do you think about this myth? Do you agree? What are your lessons learned?

Want to separate Scrum from the myths? Join our Professional Scrum Master or Scrum Master Advanced courses (in Dutch or English). We guarantee a unique, eye-opening experience that is 100% free of PowerPoint, highly interactive and serious-but-fun. Check out our public courses (Dutch) or contact us for in-house or English courses. Check out the previous episodes here (1, 2, 3, 4 , 5, 6, 7, 8).