In this article, I will share four perspectives that can help shape the structure of product groups and teams in the right way.

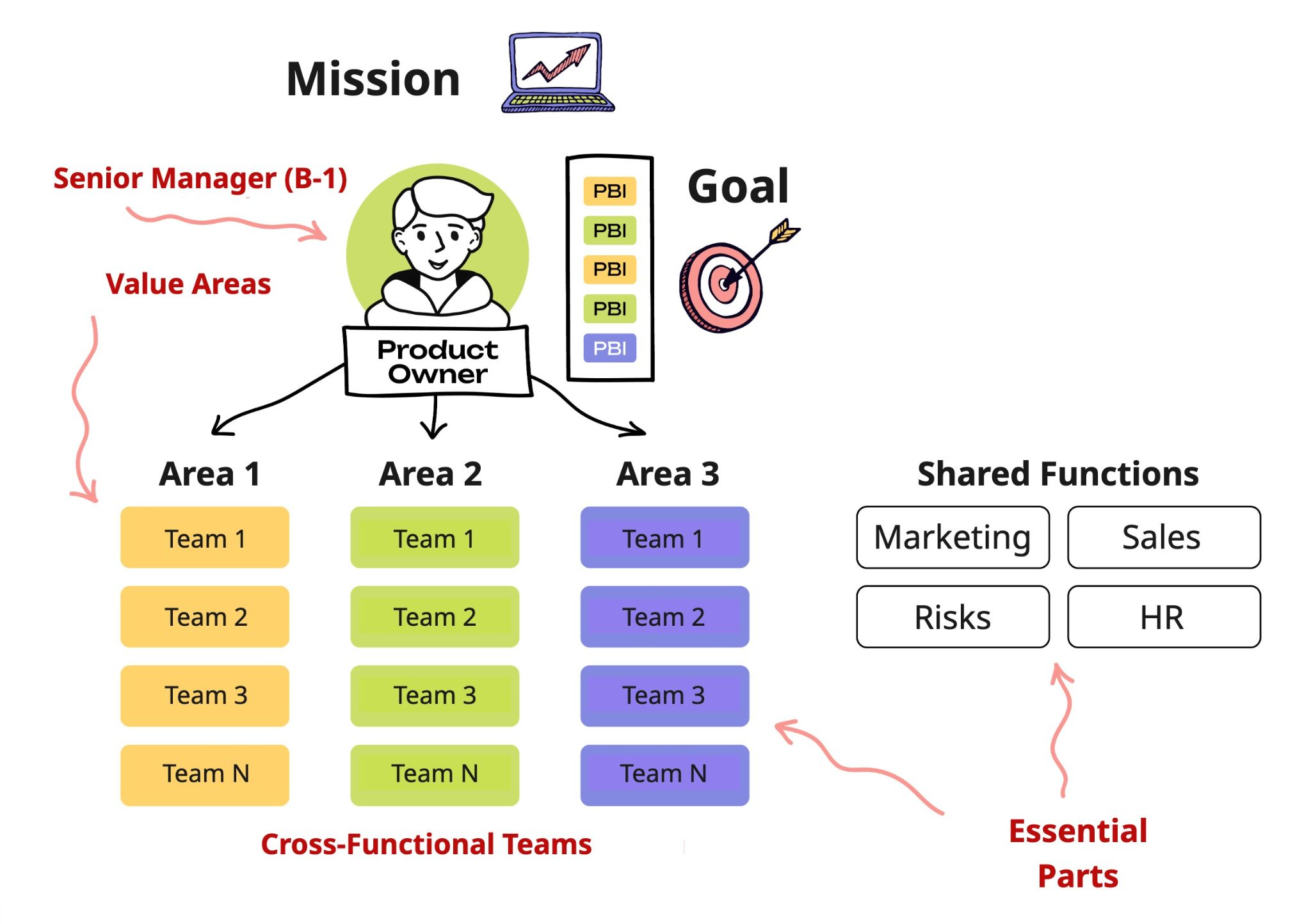

In the Creating Agile Organizations approach we defined a product group as a semi-autonomous unit built around a family of products. It contains the entire value stream. The group is led by a senior manager — the Product Owner, responsible for the strategy, vision, and business outcomes of the product line.

A product group is built from the essential parts needed to fulfill its mission. These parts could be:

- cross-functional teams (feature teams),

- shared functions or components.

Product Group prototype

Teams often specialize in specific areas of value — for example, by customer segments, Jobs-to-be-Done, or parts of the customer journey. The perspectives described below help to:

- include the right elements in a product group,

- decide what should be part of the teams and what is better left in shared functions.

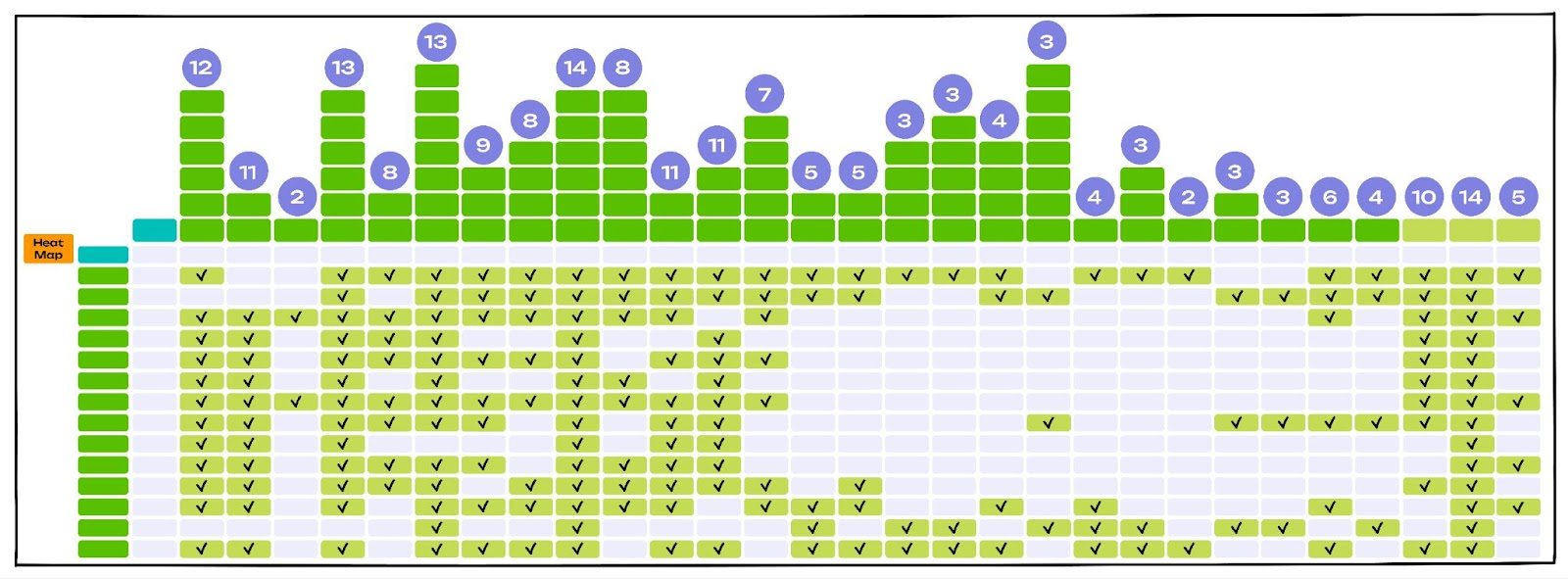

Perspective 1: Frequency (Heat Map)

This is the most common and straightforward perspective. I have been using it for more than ten years. When the boundaries of a product are defined and a Product Owner is assigned, they form the Product Backlog. You can analyze:

- architectural components,

- organizational functions.

The logic is simple: include in the product group those components and functions that most often require changes — the ones that “heat up” most frequently.

Heat Map that shows frequency of components and functions

A helpful tool here is a heat map. It shows what functions and components are required most often in the Product Backlog and helps make an initial selection.

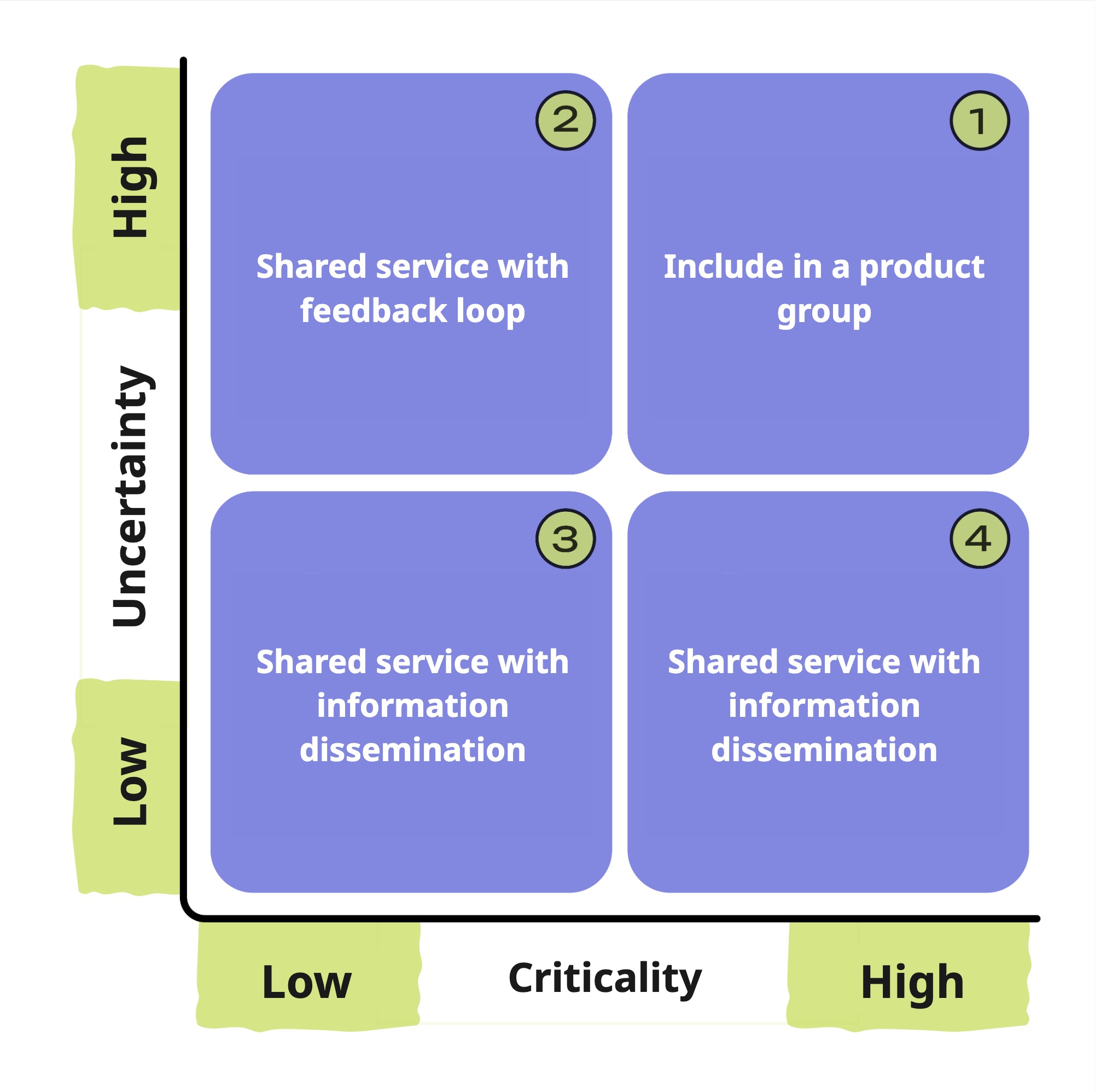

Perspective 2: Criticality and Uncertainty

Criticality is the degree to which an external component or function (outside the product group) impacts the business outcomes for which the Product Owner is accountable. For example: if your product is lending, then the risk management function is likely to be highly critical for you.

Uncertainty is the extent to which an external component or function disrupts timely and predictable value delivery. A classic example is information security. It is often centralized and not part of the product group, but it often blocks releases at the last moment and breaks plans. For your product, this means high uncertainty.

Criticality / uncertainty

I use a criticality/uncertainty matrix and evaluate each external function on a 10-point scale.

- High criticality (6–10) means a significant impact on outcomes.

- High uncertainty (6–10) means a high risk of disrupting delivery.

Functions that score high on both dimensions are recommended to be included in the product group.

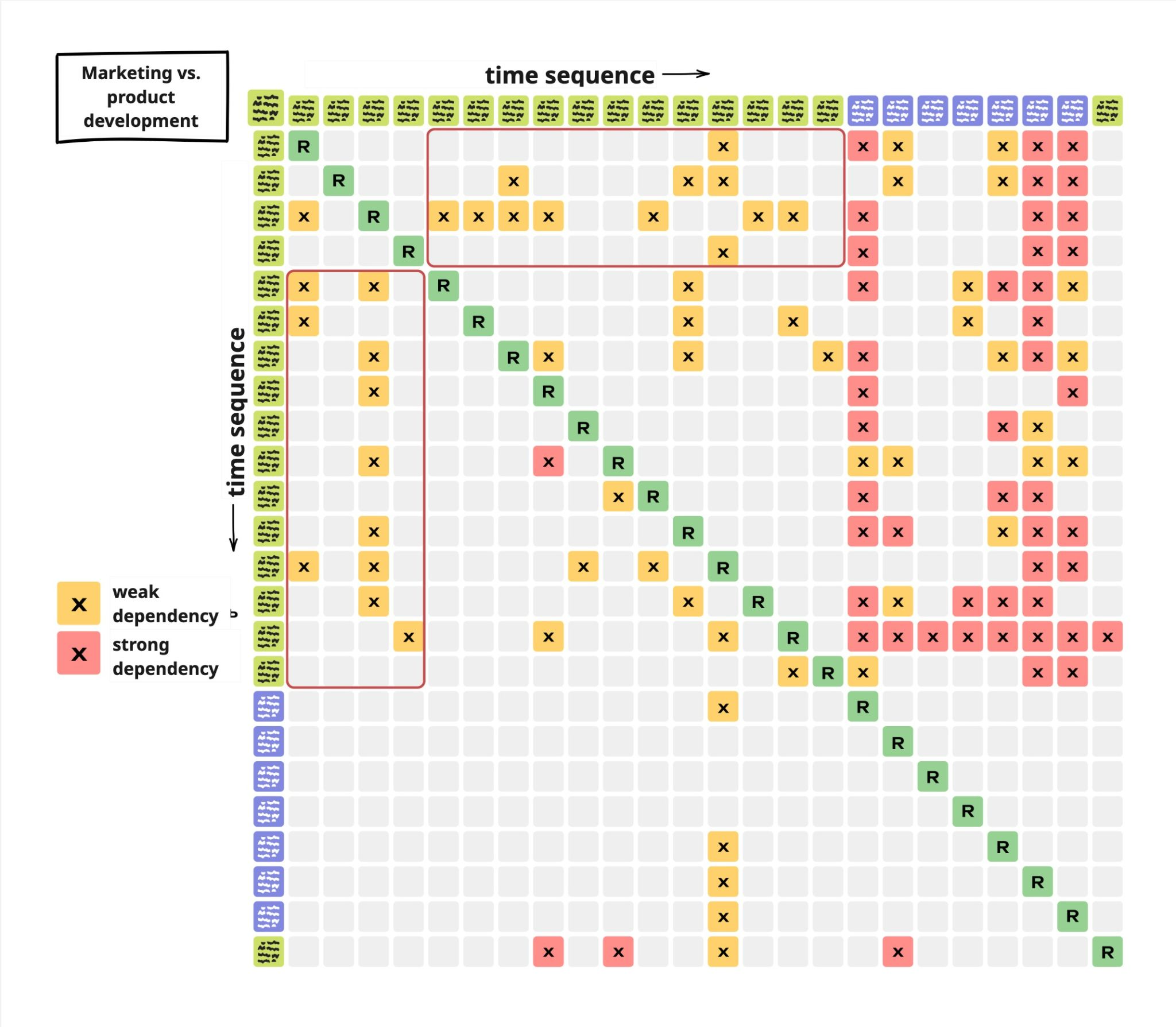

Perspective 3: Type of Operational Dependencies (DSM)

This perspective is used to fine-tune the structure of a product group. Usually, it comes after analyzing frequency and criticality/uncertainty.

Let’s recall the three types of dependencies described by James Thompson:

- Pooled,

- Sequential,

- Reciprocal.

Coordinating reciprocal dependencies is two / three times more expensive than coordinating pooled or sequential ones. That’s why it is optimal to include reciprocal dependencies in the same unit — it reduces coordination costs and simplifies collaboration.

DSM that shows dependencies between marketing and product development

To identify the type of dependencies, DSM matrices are used. Symmetrical elements relative to the diagonal indicate the presence of reciprocal dependencies.

I don’t use this perspective all the time, but only for fine-tuning. For example:

- Frequency and criticality/uncertainty do not provide a clear answer.

- You hesitate whether a component or function should be included in the product group.

- If the DSM matrix shows reciprocal dependencies, that is a strong argument for inclusion.

On the other hand, frequency alone may suggest that a function is essential (for example, marketing). But if the DSM matrix shows only pooled or sequential dependencies, and both criticality and uncertainty are low, then marketing can reasonably remain outside the product group.

Perspective 4: Cost of Delay (Value Stream Mapping)

This perspective is also useful for fine-tuning. It is important in cases where functions:

- do not appear frequently in the backlog,

- work in a predictable way,

- but still become bottlenecks for the whole organization.

This usually happens because the function is centralized and serves all product groups at once.

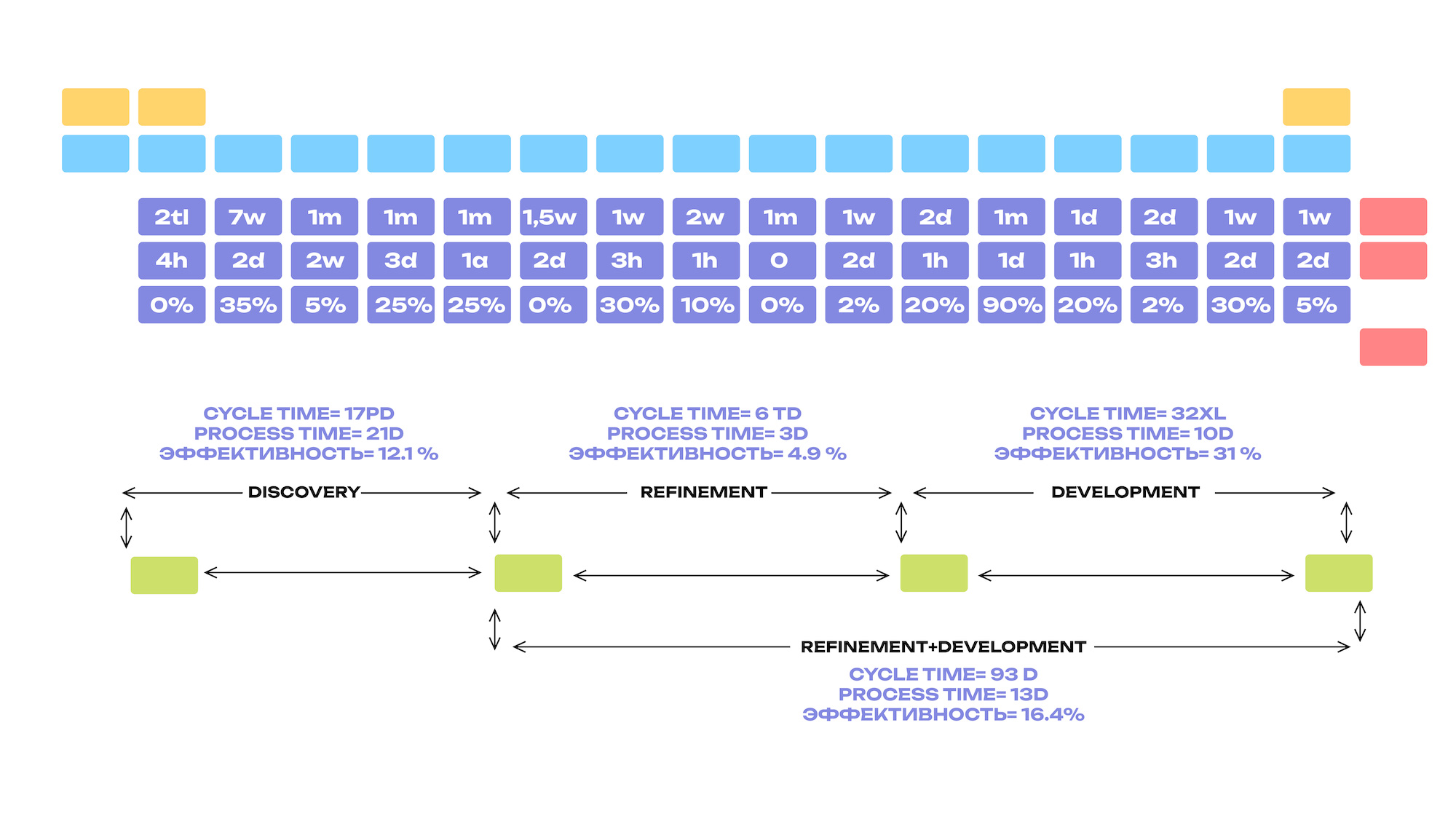

With Value Stream Mapping, you can evaluate the cost of delay.

A practical example: at one client, the legal function was delaying the flow of value creation by an average of 2–3 months. Previous attempts to include lawyers in product groups had failed. But once we evaluated the cost of delay and showed how much money was being lost because of this pause, the decision was made quickly — a lawyer was assigned to the product group.

Value-Stream Mapping (VSM)

Traditional management thinks in terms of resource efficiency (“how to keep the lawyers fully utilized”). The perspective of cost of delay shifts the conversation to flow efficiency — and in that case, the arguments become much more compelling.

How to Use All Four Perspectives

It is best not to rely on a single perspective, but to combine them. My typical approach:

- Once the product boundaries are defined and the Product Owner is appointed, I always start with frequency and criticality/uncertainty.

- I bring in the perspectives of operational dependencies and cost of delay only if needed — when doubts remain and fine-tuning is required.

This approach helps avoid endless discussions and allows you to find a balance between the autonomy of a product group and the benefits of scale and efficiency.