We often talk about products and product groups. But there's a more fundamental question to answer before diving into product group design: how aligned is your business portfolio?

In large organizations, several businesses almost always coexist simultaneously. The degree of their interconnectedness largely determines how autonomous and agile product groups can actually be. Business portfolio cohesion affects fundamental decisions:

- How much authority should be delegated from the center to operating units?

- How independent should business units be from one another?

- What level of horizontal and vertical integration is needed to achieve results?

- What role and influence should enabling functions play?

Defining portfolio cohesion is a key strategic decision that shapes your entire organizational architecture: from structure and roles, through decision-making processes, to how autonomous and agile business units and product groups can actually be.

In this article, we explore four types of business portfolio cohesion and work through how to find the right position on this continuum for your company.

Business Architecture and StructureA typical company architecture consists of several levels. At the top level sits the business portfolio—a set of business models through which the organization creates, delivers, and captures value. According to Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur's definition, a business model describes the logic of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. Consider a few examples:

- Samsung operates three primary business models: Mobile eXperience (smartphones, tablets, wearables, and ecosystem services), Visual Display (TVs, monitors, and display devices for home and business), and Digital Appliances (home appliances, kitchen devices, and smart home products).

- Amazon is structured around three key businesses: retail and marketplace in North America, the same segment outside North America (International), and Amazon Web Services (AWS)—cloud infrastructure.

Business architecture and org structure

Within each business sit product lines and individual products. Products, in turn, comprise value areas.

Note: In very large companies like Toyota or P&G, additional organizational levels—categories and brands—may exist between the business and product lines. These are omitted for simplicity.

It's important to note that business architecture is closely tied to organizational structure. Each business or business model in the organization corresponds to a separate business unit (BU) or, in very large corporations (P&G, General Electric), a strategic business unit (SBU). Product lines are developed in product groups, while work in specific value areas is carried out by teams.

Four Types of Business PortfoliosIn the 1990s, Jay Galbraith first proposed a typology of business portfolio cohesion. His ideas were later developed by Amy Kates and Kesler, particularly in their book Networked, Scaled and Agile. They propose arranging business portfolio cohesion along a continuum of four categories:

- Single integrated business (unified integrated business)

- Closely related portfolio (tightly integrated portfolio)

- Loosely related portfolio (weakly integrated portfolio)

- Holding / conglomerate (holding / conglomerate)

Four Types of Business Portfolios

Single Integrated Business

Companies of this type may have many products—like Apple—but all operate within a single business model. It's no surprise that Apple remains a functionally organized company: its business is built on a unified model and shared management system.

These companies typically have a functional structure, where heads of marketing, sales, engineering, and operations work as one team and jointly manage the business. A unified strategy is applied across all P&L divisions with minimal variation; key decisions are made centrally. Processes and practices are standardized, and a unified culture is maintained. Functional policies, talent decisions, and standards aim to build a single global functional framework. Functional cost management is centralized.

Examples: Apple, Heineken, Coca-Cola, BMW.

Closely Related Portfolio

In this category, the portfolio contains two or more businesses that are tightly linked. A typical example is a bank with retail and corporate divisions. They are deeply interconnected: many customers use both simultaneously. Moreover, both divisions rely on unified technological infrastructure, shared compliance processes, and can use the same service and sales channels. This creates significant synergies: the bank can offer cross-selling (e.g., loans to employees of corporate clients, investment products for business owners) and optimize costs through unified back-office functions and shared analytics.

It's natural that such companies have many shared IT systems and services. In a typical bank, all development (both retail and corporate) reports linearly to the CIO/CTO because the company benefits from common standards, a unified technology stack, and standardized working principles. Nevertheless, two separate business units almost always exist: retail and corporate.

In a tightly integrated business portfolio, units are not completely independent and don't contain all functions necessary for full business management. They typically focus on managing product offerings, marketing, and product development.

Examples: Deutsche Bank, UniCredit, Avito, Sber.

Loosely Related Portfolio

In this third category, business units and their strategies become more autonomous and independent.

A good example is Yandex. The company has several major business lines: search and advertising technology, e-commerce and marketplace, mobility and delivery (taxi, car-sharing, food), media and entertainment (Kinopoisk, music), cloud and B2B services, and ecosystem devices and "Alice" assistant. These directions are linked by a common brand, unified account, and usage data, but each business line develops its own markets and products, carries its own P&L, and makes independent decisions on risks and investments.

In a loosely integrated portfolio, business units are far more autonomous: most or all functional resources are "embedded" within the business unit itself and managed directly. They may still share some functions (risk, compliance, operations, brand marketing), but essentially act as independent, empowered P&L units.

Examples: 3M, Siemens, General Electric, Yandex.

Holding

Holdings or conglomerates are structured fairly simply at the group level: a small corporate center focused on talent decisions and major financial matters, and virtually independent business units. Units in this model essentially live their own lives: they report financial results to the parent company but lack common processes and differ significantly in culture. Cross-cutting corporate policies and practices are minimal, focusing mainly on risk, compliance, and fiduciary responsibility.

Pasha Group is a classic example of a holding/conglomerate. Pasha Holding is positioned as a major Azerbaijani holding controlling dozens of companies in banking, insurance, construction, real estate, tourism, technology, and investments. The structure is typical for a holding: the parent company owns controlling stakes (Kapital Bank, Pasha Bank, Pasha Insurance, Pasha Life, Pasha Construction, Absheron Hotel Group, etc.) and manages a diversified portfolio of assets across different industries and countries.

Examples: Berkshire Hathaway, Virgin Group, Tata Group.

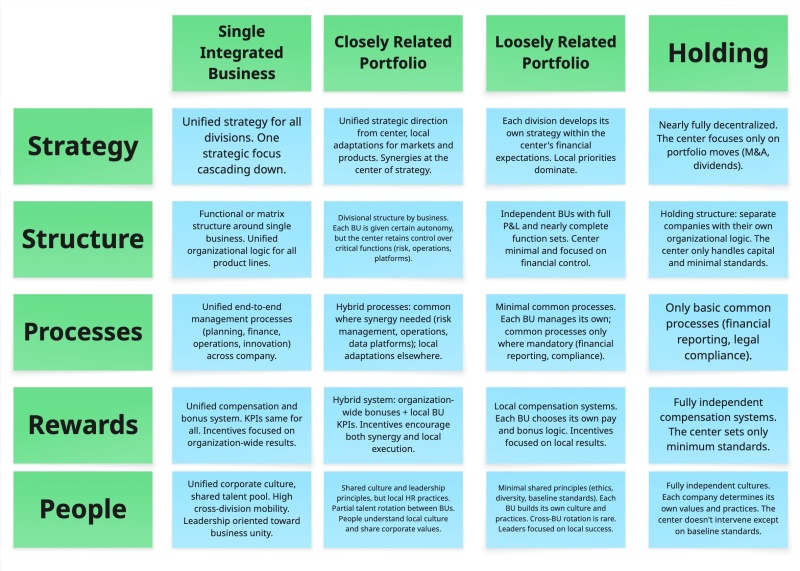

In the table below, you can see an analysis of each business portfolio type through Galbraith's Star Model.

Which Portfolio Type Should You Choose? There is no right answer. Your portfolio type choice is determined by your strategy and business nature. But it's crucial to understand the core tradeoff: the more integrated your portfolio, the more synergies, scale benefits, and corporate flexibility you gain—but you lose in local adaptability and speed. You cannot simultaneously be super-flexible at both the company-wide level and the individual BU level. You'll have to sacrifice something. This is the eternal choice between local flexibility and corporate efficiency. To find your position on this continuum, it's important to understand the pros and cons of each pole.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Decentralization

What you gain with greater unit autonomy:

- Local adaptability & customer fit. Products, UX, pricing, and channels can be quickly adapted to local context. Decisions are made close to customers and regulators, without lengthy central approvals. Local teams respond quickly to changes in demand, competition, and regulatory environment, demonstrating local adaptability without long coordination cycles.

- Local ownership and entrepreneurship. Local leaders manage resources, budgets, and results across their scope. This strengthens accountability and fosters entrepreneurial management style.

- Local innovation and disruption. Being closer to customers and emerging needs, local teams are first to spot and develop disruptive innovations for their markets. Market breakthroughs often originate locally—where a centralized organization would miss them.

What you lose with decentralization:

- Duplication of resources. Local divisions create their own marketing, analytics, UX, and engineering teams, sometimes even mini-platforms. Parallel centers of expertise and systems emerge without real economies of scale.

- Higher cost and lower return on assets. Fragmented IT landscape and duplicate support functions increase total expenses and reduce asset utilization. Each division optimizes for itself.

- Complex P&L and boundaries. The same platforms, channels, or customers often serve multiple divisions, making revenue and cost allocation difficult. Organizational conflicts arise: who "books" the revenue? Who pays for shared infrastructure?

Advantages and Disadvantages of Centralization

What you gain with greater portfolio integration:

- Fewer, bigger bets. Resources concentrate on a limited number of major initiatives, increasing chances of meaningful impact. Instead of many small projects—several powerful strategic moves.

- Fluid talent & ideas. People and best practices move more easily between business lines and geographies, creating a shared expertise pool. Knowledge spreads faster.

- Economies of scale. IT, HR, finance, data platforms, and other functions operate as shared infrastructure, delivering scale benefits and uniform quality standards.

- Enterprise adaptability. The corporate center can make portfolio-level decisions (launching, scaling, selling, or closing businesses) and quickly reallocate resources in line with evolving company priorities in a coordinated way.

- Coherent standards. Unified processes, architectures, and platforms reduce coordination costs, simplify control and compliance, and drastically limit the internal "zoo" of conflicting standards.

What you lose with centralization:

- Central bureaucracy and friction. Multi-level approvals and rigid rules slow response to change and hinder local decision-making.

- Low local speed and flexibility. Local divisions have limited authority to change products, pricing, or channels, even when they see clear opportunities or risks.

- Low local adaptability and decision quality. Decisions are made far from customers, partners, and regulators. Important local signals are filtered or delayed, undermining decision quality.

- Weaker accountability. When key decisions and resources sit in the center, local leaders feel less responsible for results. This weakens entrepreneurship and negates local adaptability benefits, even when formally permitted.

Understanding these tradeoffs is the foundation for choosing your company's right position on the portfolio continuum.

Diagnostic Tool

The final step is to understand how aligned your portfolio is: whether your strategic choice of portfolio type, actual operating model, and the centralization/decentralization effects you currently feel in the organization all align. Use this simple set of questions:

1. What portfolio type matches our strategy?

First, answer not about what exists now, but about what should be. Based on strategic ambitions, market nature, and customer needs, determine which portfolio archetype makes strategic sense: Single Integrated Business, Closely Related Portfolio, Loosely Related Portfolio, or Holding.

It's important to fix your target state: if you were designing the company from scratch for your current strategy, where would you place yourself on the continuum?

2. What portfolio type do we actually have right now?

Next, examine reality through Galbraith's Star Model lens. For each of five elements (Strategy, Structure, Processes, Rewards, People), determine which archetype you're actually closest to—not in presentations, but in practice. Often you'll find that strategy declares, say, Closely Related Portfolio, while structure, processes, and reward systems behave like Loosely Related Portfolio or even Holding. This is your first diagnostic "gap."

3. Which centralization and decentralization advantages and disadvantages are critical for us? What are we willing to accept?

Using the centralization/decentralization effects list, identify which benefits are non-negotiable for you (e.g., local adaptation or scale efficiency) and which drawbacks you're prepared to tolerate.

At this stage, it's important to honestly acknowledge:

- Where you're willing to sacrifice local flexibility for integration and synergies,

- And where, conversely, you're prepared to forgo some scale and standardization for entrepreneurship and BU-level speed.

Your answers set the political and cultural boundaries of possible design.

4. What changes to the Star Model elements will close the gap?

Once your target portfolio type, current state, and acceptable tradeoffs are clear, return to Galbraith's Star and ask the most practical question: what specific changes in Structure, Processes, Rewards, and People will move you from your current archetype to the target?

- In structure — which functions and decisions make sense to centralize (e.g., risk, finance, IT platforms, brand), and what should intentionally stay at the BU level (products, local marketing, P&L management)?

- In processes — what new horizontal connections, joint forums, and integration and coordination processes need to be established between BUs and center (shared committees, cross-BU initiatives, unified planning and prioritization cycles)?

- In rewards — which KPIs and bonuses should drive the right balance between synergy (shared goals) and local accountability (BU results)?

- In people and culture — which leadership behaviors, habits, and cultural norms should be strengthened (e.g., willingness to share resources, portfolio thinking), and which weakened?

This element-by-element breakdown transforms the conversation from "we want to be more like a Closely Related Portfolio" into a concrete change plan: exactly what to strengthen at the center, what to push to BU level, and what new connections between them are needed so the portfolio and operating model finally align.