TL; DR: Mechanical Ceremonies to Meaningful Events

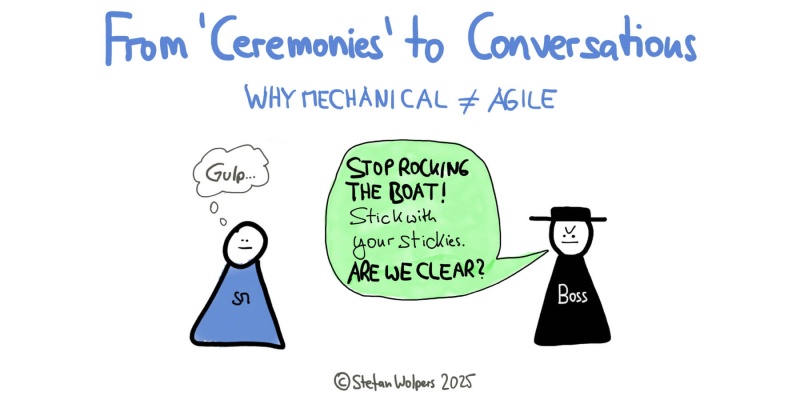

Your Agile events aren’t failing because people lack training. They’re failing because your organization adopted the rituals while rejecting the transparency, trust, and adaptation that make them work. And often, the dysfunction of mechanical ceremonies isn’t a bug. It’s a feature.

The Reality of Your “Ceremonies”

Let’s stop pretending. Your Daily Scrum is a status report. Your Sprint Planning confirms decisions that a circle of people made last week without you. Your Retrospective surfaces the same three issues it surfaced six months ago, and nothing has changed. Your Sprint Review is a demo followed by polite applause, before everyone happily leaves to do something meaningful.

You know this. Everyone knows this. And yet tomorrow morning, you’ll do it all again.

What I described is what mechanical Agile looks like. The organization bought the artifacts, sent people to training, installed Jira, and declared itself agile. The “ceremonies” happen on schedule. The Sprint board exists, and management assigned the roles. And none of it produces the outcomes Agile was supposed to deliver, because the organization adopted the rituals while rejecting the requirements that make them work.

Practicing Agile, for example, Scrum, without understanding its purpose, isn’t just ineffective. It’s harmful.

The Comfortable Lie

When “ceremonies” become theater, organizations reach for easy answers: more training, a different Retrospective format, better tools, or another workshop. These aren’t bad things. But they’re often used as substitutes for the harder work of changing how the organization actually operates.

Training teaches you the mechanics. Ist can’t make your organization and your people safe for transparency or create trust among each other.

The reason your events feel hollow isn’t that people don’t understand Scrum or Agile principles. It’s that your organization hasn’t created the conditions where transparency, inspection, and adaptation can actually occur.

Many organizations achieve some transparency: the Sprint boards exist, and the Product Backlogs are refined and accessible. Some achieve inspection: people look at the data, discuss what’s there, nod thoughtfully. Almost none achieve adaptation: actually changing course based on what they have learned.

That’s where organizations fail, because adaptation is politically dangerous.

Adaptation means admitting the plan was wrong. It means telling a stakeholder their pet feature isn’t shipping. It means saying “I don’t know” in a room full of people who interpret uncertainty as incompetence. It means surfacing problems that powerful people would prefer stayed buried.

No Retrospective format fixes this. No amount of training overcomes it. The dysfunction isn’t a skills gap. It’s a trust gap.

What Nobody Wants to Admit

Interestingly, and we rarely talk about it, the theater persists because it serves someone’s interests.

Managers get status reports without having to ask for them. Leadership gets the appearance of predictability. Teams get protection from accountability. Everyone gets to check the “we’re agile” box without any of the discomfort that genuine agility requires.

Consider the manager’s dilemma. Their incentives reward demonstrating control, filtering bad news before it travels upward, and projecting predictability. Agile asks the opposite: surface problems early, admit uncertainty, escalate impediments publicly. Why would any rational manager do that in an organization that punishes the messenger?

Ritual is safer than honesty. That’s the deal everyone has quietly accepted.

I’ve worked with teams where the Retrospective had been running for two years without producing a single meaningful change that originated from an impediment. Two years. The same issues came up, got documented, and died in a Jira “action item backlog” nobody looked at. When I asked why, the Scrum Master shrugged: “We don’t have the authority to fix anything. We just identify problems.”

That’s not a Retrospective. That’s a venting session with post-its at the core of all mechanical ceremonies performed in your organization.

The Fundamental Confusion

We are not paid to practice Scrum.

Read that again. We are not paid to practice Scrum. We are paid to solve customer problems within given constraints while contributing to our organization’s sustainability. Scrum is a means, not an end. The moment you optimize for “doing Scrum correctly” instead of delivering value, you’ve lost the plot.

Each Scrum event exists to enable a specific conversation:

- The Daily Scrum: Are we on track for the Sprint Goal? What needs to change today?

- Sprint Planning: What are we committing to? Do we have a credible plan?

- Sprint Review: Did we build the right thing? What did we learn?

- Retrospective: What will we actually change?

Not rituals. Conversations. When the conversation dies, and only the ritual remains, you get decision displacement (real choices happen elsewhere), performance theater (people demonstrate compliance rather than solve problems), and ritual without belief (teams going through motions they stopped believing in long ago).

The cargo cult version of Agile or Scrum doesn’t just fail to help. It actively harms. It teaches people that process is something to endure. It immunizes organizations against agility by leading them to believe they’ve tried it and it didn’t work. It turns good practitioners into cynics.

Obvious Red Flags of Mechanical Ceremonies You’re Ignoring

Watch for these: Retrospectives that finish in under 30 minutes. Action items that never close. Sprint Review attendance is dropping. Refinement sessions where nobody challenges estimates. Daily Scrums where people multitask. (Check out the Scrum Anti-Patterns Guide below; it is a whole book on these red flags.)

These aren’t engagement problems. They’re trust problems wearing an engagement costume. People have learned that showing up fully isn’t safe or isn’t worthwhile.

Ask yourself honestly: Can you tell your manager this Sprint is at risk without negative consequences? Can you say “I don’t know” in planning? Can you escalate an impediment and expect it actually to get addressed?

If not, you’re asking your team to take risks you won’t take yourself.

Psychological safety isn’t about comfort. It’s about whether you can take interpersonal risks without retaliation. Admit a mistake. Challenge a decision. Raise an uncomfortable truth. Without that, every “ceremony” in your organization becomes a performance where self-protection is the goal.

Conclusion

The transformation from mechanical ceremonies to meaningful Agile conversations isn’t a technique. It’s relational. It requires leaders who reward transparency over theater, who can distinguish real problems from incompetence, who model the vulnerability they’re demanding from others.

It also requires practitioners willing to go first. To say the thing everyone is thinking. To stop playing along with the fiction.

None of this is easy. The incentives push toward compliance, toward telling people what they want to hear, toward safe topics in safe formats. Genuine agility asks you to push back, every day, in small moments that accumulate into culture.

So here’s the uncomfortable question: In the “ceremonies” you facilitate or attend, are you part of the problem?

Not the organization. Is it you?

Are you raising the issues that matter, or choosing safe topics? Challenging fictional estimates, or letting them pass? Following through on actions, or letting them quietly die? Have you ever asked yourself how you may have contributed to the current state?

It’s easy to blame the system. The system deserves blame. But somewhere in your next Daily Scrum or Retrospective, there will be a moment where you could have an honest conversation instead of performing a ritual.

What you do with that moment is the only thing you control.

🗞 Shall I notify you about articles like this one? Awesome! You can sign up here for the ‘Food for Agile Thought’ newsletter and join 40,000-plus subscribers.