The way a Product Owner influences the Product Backlog, the product, and its value is through making decisions or neglecting them (remember that a lack of decision is also a decision). The article explores the topic of decision paralysis and ways to overcome it by identifying one of two main types of decisions that Product Owners make. Decision-making is the bread and butter of product team members. This article is relevant not only for the Product Owner but for all people engaged in product development.

In the following paragraphs, I will present a thinking process that will help explore this topic. I will start with the importance of decision-making and then define the problem and hypothesis, linking them with the product and empirical product development. Then, I will explain why decisions are vital in empirical product development. Afterwards, I will examine decision paralysis as a common challenge faced by product teams. Finally, the solution to overcome this challenge will be proposed, along with some practical coaching questions to help address it.

Problem

Let’s define a problem as a specific challenge or ‘pain point’ that represents the gap between a customer’s current state and their desired goal. In product development, this problem becomes the foundation for designing a whole product or its feature that offers value by directly addressing that need. A problem typically reflects uncertainty about market conditions, customer needs, or business process effectiveness. For example:

- How can we increase customer retention?

- Does improving the user interface lead to higher sales?

These are important questions, but they are too general to be tested directly.

Hypothesis

A hypothesis, on the other hand, is a focused, testable statement that proposes a specific relationship between actions and outcomes. It translates the broad problem into something that can be validated with data. For instance:

- If we simplify the checkout process by reducing the number of steps from five to three, the conversion rate will increase by at least 10%.

- Offering personalised product recommendations will increase repeat purchases by 15% over three months.

The value of a hypothesis is that it directs investigation. It tells product teams what to measure, which data to collect, how to evaluate success, and what the next product increment might look like. Unlike a problem, which is too abstract, a hypothesis gives clear guidance for empirical testing and decision-making.

Product

A product is any good, service, or solution that a business offers to the market, intending to solve a customer problem or address a need or desire. This concept includes both tangible items (like physical devices) and intangible offerings (such as software, services, or experiences) (Leland 2025). A product is any offering that a business provides in response to a specific customer problem or need. It is a solution that bridges the gap between a customer’s current challenge and their desired outcome, delivering tangible value and satisfying measurable demand.

Empirical Product Development.

Empiricism is the principle that knowledge comes from direct observation and experience rather than assumption or intuition. In product development, this means that decisions should be based on experiments, customer feedback, and measurable outcomes instead of relying only on gut feeling or internal opinions. Empirical product development applies this principle by treating new ideas as hypotheses that must be tested in the real world. This process typically follows four key steps:

- Identify the problem. A broad business question or uncertainty.

- Formulate hypotheses. Specific, testable statements derived from the problem.

- Test empirically. Run experiments, collect data, and learn from customer behaviour.

- Adapt and iterate. Refine the product based on evidence, not assumptions.

This approach ensures that product development is guided by evidence, reduces the risk of failure, and increases the chances of creating solutions that truly meet customer needs. Problems spark curiosity, hypotheses create focus, and empiricism provides the discipline to validate ideas through measurable results.

Decision as a bridge

In empirical product development, this process can only work effectively when decisions are made at each step. Decisions are the bridge between problems, hypotheses, andproducts. A problem identifies the customer’s challenge. A hypothesis translates the problem into a testable statement. A product is designed as a solution to that problem. Decisions determine how the organisation proceeds: which hypotheses to test, which experiments to run, how to allocate resources, and how to inspect and adapt based on results.

Decision Paralysis in Product Development

One of the key challenges in modern product development is decision paralysis. Decision paralysis is the inability to move forward because teams or leaders hesitate to make choices. Research shows that 64% of executives report that decision-making has become more complex than ever, and 49% admit that decisions are delayed too often, largely due to outdated processes and risk aversion (Peak 2021).

This aligns with the well-known concept of analysis paralysis, overanalysing options to the point that no decision is made. In product teams, this often means projects stall in planning instead of reaching customers.

As one founder put it:

“Analysis-paralysis is the anti-pattern where startups become so obsessed with making the perfect decision that they fail to make any decision—or don’t make it fast enough.”

How to overcome Decision Paralysis?

One effective way to address decision paralysis in product development that helps some of the teams I was working with is by applying the distinction between Type 1 and Type 2 decisions (Bezos 2015) definition to be defined below. By recognising whether a choice is irreversible or reversible, teams can make their decision-making approach more effective. This distinction not only reduces the fear of moving forward but also empowers teams to act faster where the risk is low, while reserving deep analysis and deliberation for the rare cases where the consequences are truly long-term.

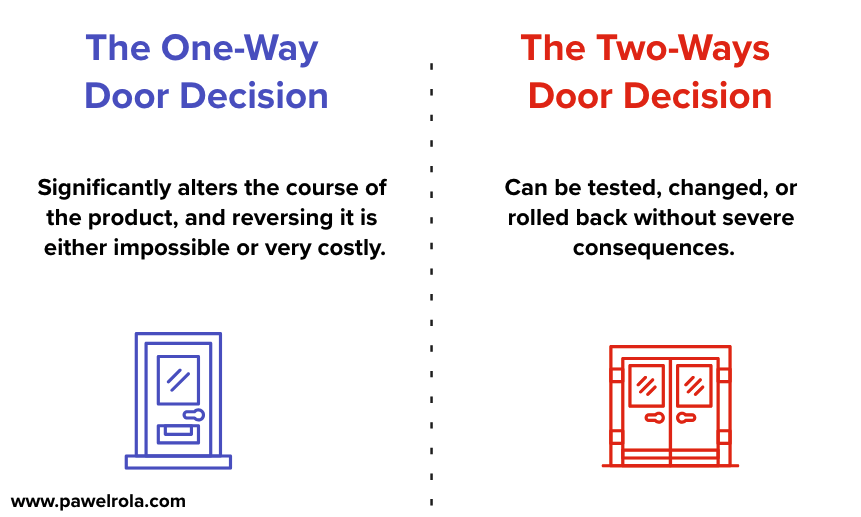

Fig 1. Two types of decisions Source: (Bezos 2015) Own elaboration

Type 1 Decision (One-Way Door)

A Type 1 decision is -stakes, consequential, and nearly irreversible choice. Once made, it significantly alters the course of the organisation or product, and reversing it is either impossible or very costly. Such decisions should be approached methodically, with careful analysis, deliberation, and broad consultation. (Bezos 2015)

Type 2 Decision (Two-Way Door)

A Type 2 decision is a reversible and lower-risk choice. It can be tested, changed, or rolled back without severe consequences. These decisions should be made quickly, ideally by individuals or small teams with sound judgment, because their reversible nature allows for experimentation and learning. (Bezos 2015)

How to Identify the Type of Decision?

Type 2 decisions are the most common decisions made by the product teams. Most product choices, such as experimenting with a new feature, adjusting pricing, or running an A/B test, are reversible. They fit the empirical mindset because they allow fast learning through experimentation without locking the company into an irreversible path.

By contrast, Type 1 decisions are rarer but have a greater impact. For example, entering a new market or pivoting the business model is far less reversible.

For organisations following empirical product development, distinguishing between Type 1 and Type 2 decisions helps maintain agility: move fast where it is safe to experiment, and slow down only where choices truly shape the long-term trajectory of the product or the company. When categorising decision types, we can consider several key characteristics: reversibility, impact, risk level, scope, speed and learning opportunities. The following set of sample questions to clarify the decision type and break the impasse can be helpful:

Reversibility

- If we make this decision and it turns out poorly, can we undo it or adjust easily?

Impact:

- Will this choice fundamentally change our product, market position, or strategy?

Risk Level

- What is the cost of being wrong—time, money, customer trust?

Scope

- Does this decision affect only a small feature/team, or does it impact the entire organisation?

Speed

- If we delay, do we risk missing a critical opportunity?

Learning Opportunity

- Can we treat this as an experiment to generate data and insights?

Conclusions

Clearly defining the real problems and the solutions created to address them is crucial for the success of any organisation. Addressing customers’ genuine problems innovatively and building a business based on solving these problems have proved to be key factors in companies’ long-term success. It helps organisations like Netflix, Uber, and Spotify revolutionise their respective fields and have a long-lasting impact on society (Rola 2025).

Decisions are enablers to any product development activity; overcoming decision paralysis is a real problem for many Product Owners and Product Teams.

Are you optimising for perfect decisions, or are you optimising for decisions that enable perfect outcomes over time? This article presents a solution that can help to solve this challenge. If you found this article helpful, explore more content at pawelrola.com. Feel free to contact me via LinkedIn or the website.

Let’s work together to bring the organisations of the future.

This article was originally published at: pawelrola.com Direct LinkBibliography

Bezos, Jeffrey P. 2015. “amazon.com.” https://ir.aboutamazon.com/annual-reports-proxies-and-shareholder-letters/. https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/annual/2015-Letter-to-Shareholders.PDF.

Leland. 2025. Leland. June 13. https://www.joinleland.com/library/a/what-is-a-product-and-how-to-start-building-one?

Peak. 2021. Going nowhere fast: Two-thirds of UK CEOs experience ‘Decision Paralysis’, and over half regret a major business decision . 03 22. https://peak.ai/hub/blog/decision-intelligence-report-two-thirds-of-uk-ceos-experience-decision-paralysis-and-over-half-regret-a-major-business-decision/.

Rola, Pawel. 2025. pawelrola.com. 02. https://pawelrola.com/leaders-business-innovation-improve-pratice/.