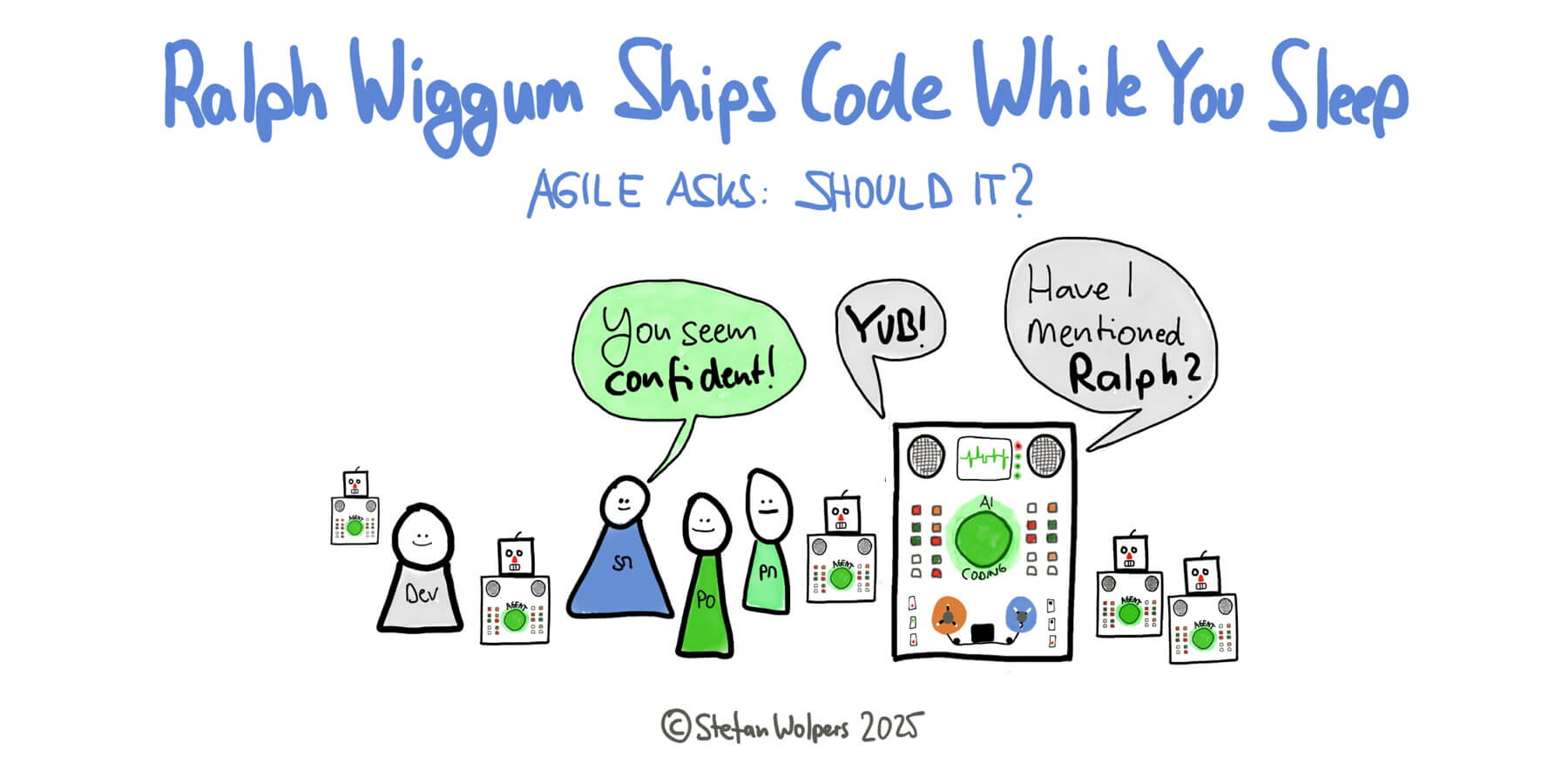

TL; DR: When Code Is Cheap, Discipline Must Come from Somewhere Else

Generative AI removes the natural constraint that expensive engineers imposed on software development. When building costs almost nothing, the question shifts from “can we build it?” to “should we build it?” The Agile Manifesto’s principles provide the discipline that these costs used to enforce. Ignore them at your peril when Ralph Wiggum meets Agile.

The Nonsense about AI and Agile

Your LinkedIn feed is full of confident nonsense about Scrum and AI.

One camp sprinkles "AI-powered" onto Scrum practices like seasoning. They promise that AI will make your Daily Scrum more efficient, your Sprint Planning more accurate, and your Retrospectives more insightful. They have no idea what Scrum is actually for, and AI amplifies their confusion, now more confidently presented. (Dunning-Kruger as a service, so to speak.)

The other camp declares Scrum obsolete. AI agents and vibe coding/engineering will render iterative frameworks unnecessary, they claim, because software creation will happen while you sleep at zero marginal cost. Scrum, in their telling, is rigid dogma unfit for a world of autonomous code generation; a relic in the new world of Ralph Wiggum-style AI development.

Both camps miss the point entirely.

The Expense Gate Ralph Wiggum Eliminates

For decades, software development had a natural constraint: engineers were expensive. A team of five developers cost $750,000 or more annually, fully loaded. That expense imposed discipline. You could not afford to build the wrong thing. Every feature required justification. Every iteration demanded focus.

The cost was a gate. It forced product decisions.

Generative AI removes that gate. Code generation approaches zero marginal cost. Tools like Cursor, Claude, and Codex produce working code in minutes. Vibe coding turns product ideas into functioning prototypes before lunch.

The trend is accelerating. Consider the "Ralph Wiggum" technique now circulating on tech Twitter and LinkedIn: an autonomous loop that keeps AI coding agents working for hours without human intervention. You define a task, walk away, and return to find completed features, passing tests, and committed code.

The promise is seductive: continuous, autonomous development in which AI iterates on its own work until completion. Geoffrey Huntley, the technique's creator, ran such a loop for three consecutive months to produce a functioning programming language compiler. [1] Unsurprisingly, the marketing writes itself: "Ship code while you sleep."

But notice what disappears in this model: Human judgment about what is worth building. Review cycles that catch architectural mistakes. The friction that forces teams to ask whether a feature deserves to exist. As one practitioner observed about these autonomous loops: "A human might commit once or twice a day. Ralph can pile dozens of commits into a repo in hours. If those commits are low quality, entropy compounds fast." [2]

The expense gate is gone. The abundance feels liberating. It is also dangerous.

Without the expense gate, what prevents teams from running in the wrong direction faster than ever? What stops organizations from generating mountains of features that nobody wants? What enforces the discipline that cost used to provide?

The Principles Provide the Discipline

The answer is exactly what the Agile Manifesto was designed to provide.

Start with the first value: "Working software over comprehensive documentation." In an AI world, generating documentation is trivial. Generating working software is trivial. But generating working software that solves actual customer problems remains hard. The emphasis on "working" was never about the code compiling. It was about the software doing something useful. That distinction matters more now, not less.

Then there is simplicity: "the art of maximizing the amount of work not done." When engineers cost $150K annually, leaving out features of questionable value saved money. Now that building costs almost nothing, leaving features out requires discipline rather than economics. The product person who asks "should we build this?" instead of "can we build this?" becomes more valuable, not less.

"Working software is the primary measure of progress." AI can generate a thousand lines of code per hour. None of those represents progress itself. Instead, progress is measured by working software in users' hands who find it useful. Customer collaboration and feedback loops provide that measurement. Output velocity without validation is a waste at unprecedented scale.

And then technical excellence: "Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility." This principle now separates survival from failure.

The Technical Debt Trap

Autonomous AI development produces code that works well enough to ship. The AI generates plausible implementations that pass tests and satisfy immediate requirements. Six months later, the same team discovers the horror beneath the surface. You build it, you ship it, you run it. And now you maintain it.

This is "artificial" technical debt compounding at unprecedented rates.

The Agile Manifesto called for "sustainable development" and for teams to maintain "a constant pace indefinitely." These were not bureaucratic overhead invented by process enthusiasts. They were survival requirements learned through painful experience.

Organizations that abandon these principles because AI makes coding cheap will discover a familiar pattern: initial velocity followed by grinding slowdown. The code that was so easy to generate becomes impossible to maintain. The features that shipped so quickly become liabilities that cannot be safely modified.

Technical excellence is not optional in an AI world. It is the difference between a product and a pile of unmaintainable code.

The "Should We Build It" Reframe

The fundamental question of product development has always been: are we building the right thing?

When building was expensive, the expense itself forced that question. Teams could not afford to build everything, so they had to choose. Product people had to prioritize ruthlessly. Stakeholders had to make tradeoffs.

Now that building is cheap, the forcing function is gone. Organizations can build everything. Or at least they think they can.

The pressure compounds from above. Management and stakeholders are increasingly factoring in faster product delivery enabled by AI capabilities. Late changes that once required difficult conversations now seem costless. Prototypes that once took weeks can appear in hours. The expectation becomes: if AI can build it faster, why are we not shipping more? This pressure makes disciplined product thinking harder precisely when it matters most.

The Agile Manifesto's emphasis on "customer collaboration" and "responding to change" exists precisely because requirements emerge through discovery, not specification. Feedback loops with real users matter more when teams can produce working software faster. Without those loops, teams generate features in a vacuum, disconnected from the people who must find them valuable.

The product person who masters this discipline becomes irreplaceable. The product person who treats the backlog as a parking lot for every idea becomes a liability at scale, approving AI-generated waste faster than ever before.

What Stays, What Changes in the Age of Ralph Wiggum & Agile

The core feedback loops remain essential: build something small, show it to users, learn from the response, adapt. That rhythm predates any framework. It will outlast whatever comes next.

Iteration cycles may compress. If teams can produce meaningful working software in days rather than weeks, shorter cycles make sense. The principle remains: deliver working software frequently. The specific cadence adapts to capability.

The challenge function becomes more critical, not less. In effective teams, Developers have always pushed back on product suggestions: "Is this really the most valuable thing we can build to solve our customers' problems?" This tension is healthy. Life is a negotiation, and so is Agile. When AI can generate implementation options in minutes, this challenge function becomes the primary source of discipline. The question shifts from "how long will this take?" to "should we build this at all?" and "how will we know it works?"

Customer feedback loops matter more when velocity increases. These loops have always been about closing the gap between what teams build and what customers need, inspecting progress toward meaningful outcomes, and adapting the path when reality contradicts assumptions. When teams can produce more working software faster, these checkpoints become sharper. The question shifts from "look what we built" to "based on what we learned, what should we build next?"

Daily coordination adapts in form, not purpose. The goal remains: inspect progress and adapt the plan. Standing in a circle reciting yesterday's tasks has always been useless compared to answering: are we still on track, and what is blocking us? Now, it becomes critical: faster implementation cycles make frequent synchronization more important, not less.

Technical discipline becomes survival, not overhead. The harder problem is helping teams maintain quality standards when shipping is frictionless. Practitioners who can spot AI-generated code smell, who insist on meaningful review, who protect quality definitions from erosion under delivery pressure: these people become more valuable. Those who focus primarily on the "process," delivered dogmatically, become redundant.

Product accountability becomes the constraint, and that is correct. When implementation is cheap, product decisions become the bottleneck. The person who can rapidly validate assumptions, say no to plausible but valueless features, and maintain focus becomes the team's most critical asset.

These are adaptations, not abandonment. The principles survive because they address a permanent problem: building software that solves customer problems in complex environments. AI changes the cost structure. It does not change the problem.

We Are Not Paid to Practice Scrum

I have said this before, and it applies directly here: we are not paid to practice Scrum. We are paid to solve our customers' problems within the given constraints while contributing to the organization's sustainability.

Full disclosure: I earn part of my living training people in Scrum. I have skin in this game. But the game only matters if Scrum actually helps teams deliver value. If Scrum helps accomplish your goals, use Scrum. If parts of Scrum no longer serve that goal in your context, adapt. The Scrum Guide itself says Scrum is a framework, not a methodology. It is intentionally incomplete.

The "Scrum is obsolete" camp attacks a caricature: rigid ceremonies enforced dogmatically without regard for outcomes. That caricature exists in some organizations. It is not Scrum. It is a bad implementation that the Agile Manifesto warned against in its first value: "Individuals and interactions over processes and tools."

The question is not whether to practice Agile by the book. The question is whether your team has the feedback loops, the discipline, and the customer focus to avoid building the wrong thing at AI speed. If you have those things without calling them Agile, fine. Call it whatever you want. The labels do not matter. The outcomes do.

If you lack those things, AI will not save you. It will accelerate your failure.

Conclusion: Do Not Outsource Your Thinking

The tools have changed. The fundamental challenge has not.

Building software that customers find valuable, in complex environments where requirements emerge through discovery rather than specification, remains hard. The expense gate is gone, but the need for discipline remains.

The Agile Manifesto's principles provide that discipline. They are not relics of a pre-AI world. They are the antidote to AI-accelerated waste.

Do not outsource your thinking to AI. The ability to generate code instantly does not answer the question that matters.

Just because you could build it, should you?

What discipline has replaced the expense gate in your organization? Or has nothing replaced it yet? I am curious.

Ralph Wiggum & Agile: The Sources

🗞 Shall I notify you about articles like this one? Awesome! You can sign up here for the ‘Food for Agile Thought’ newsletter and join 35,000-plus subscribers.