Every product begins somewhere. Sometimes with a business plan, sometimes with a late-night brainstorming session, but more often than not… with frustration, a sudden "click" because of nature, or a spot of market gaps.

In our Scrum class (or really, any proper product management class), we talk a lot about empiricism, making decisions based on what is real, observable, and validated. But before you can validate anything, you need something to test. That’s where sparks come in.

In The Anatomy of a Product (available December 1st), we describe the Spark of Life as the origin point of any product. Sparks can be diverse:

Frustration with an existing situation (Dropbox’s founder forgetting his USB stick).

Social or cultural shifts (the rise of remote work and digital whiteboards).

Market gaps that nobody else is addressing (Spanx turning a personal need into a billion-dollar company).

Technological advancements that suddenly make new things possible (the iPhone’s multi-touch screen).

Even accidental discoveries (penicillin, microwaves).

These sparks are messy, human, and unpredictable. They rarely look like a polished vision statement. Instead, they’re flashes of possibility. That flash of possibility is often what draws people to them.

Why Sparks Matter in Complex Environments

Scrum thrives in complex domains, where cause and effect are only clear in hindsight. In those environments, products don’t emerge from Gantt charts; they emerge from sparks.

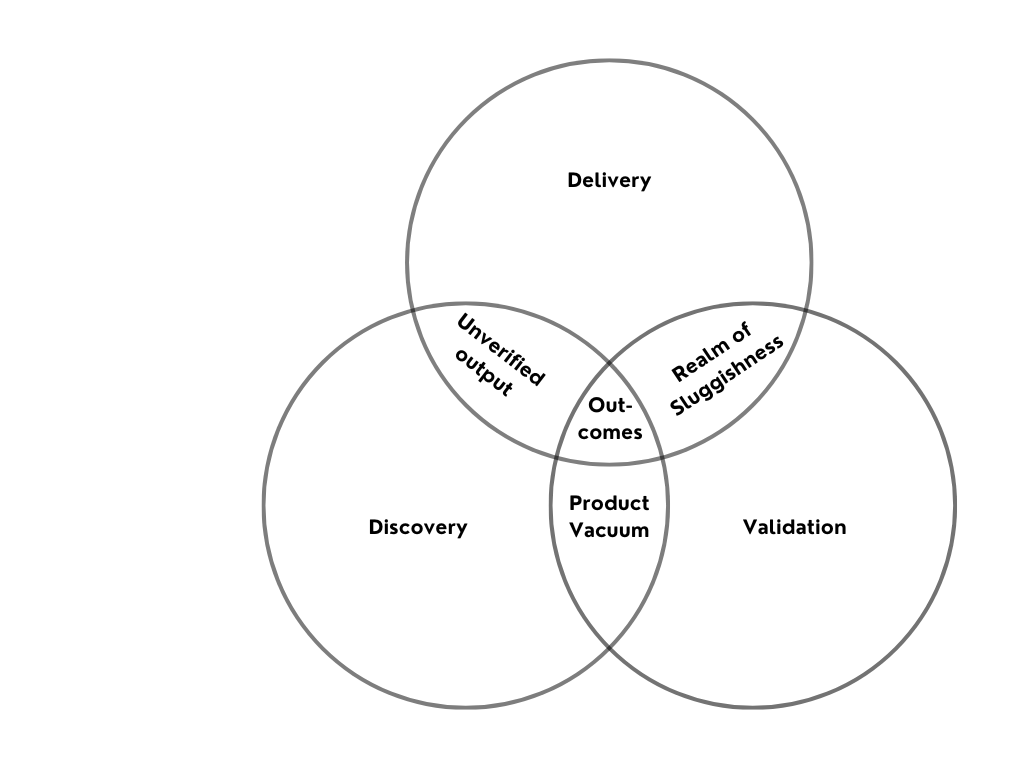

However, the danger is that organizations often treat sparks as if they were finished products. Someone says, “I’ve got a great idea!” and suddenly there’s a backlog, a roadmap, and funding, all before anyone has validated the problem. This is where waste creeps in. Teams become busy building something, but not necessarily the right thing.

Scrum Teams can treat sparks differently: as hypotheses, not certainties. A spark is not a product. It’s the invitation to explore whether there’s value worth pursuing.

From Spark to Empiricism

So how do we handle sparks responsibly? Three easy practices to help you;

1. Observe Before You Build

Scrum encourages transparency. That means making problems visible, not just solutions. Before committing to code, watch how users behave. What do they struggle with? Where are the workarounds? What are they trying to achieve? Observing behavior is cheap, low-effort, yet provides valuable insights.

In TAP, we describe sparks as tensions. The spark of Uber wasn’t “let’s build an app.” It was the frustration of not being able to get a taxi on a snowy Paris night. The solution emerged later. For Scrum Teams, the lesson we want to deliver is: don’t let the backlog fill up with half-baked solutions. Start with the spark, and keep reflecting on whether you are fixing that problem, frustration, gap, or possibility.

2. Frame the Problem Clearly

A spark needs framing to become useful. Otherwise, it dies out or mutates into feature bloat. A strong problem statement creates alignment:

“[Target user/group] is experiencing [observable challenge] in [specific context], which leads to [negative outcome].”

This is simple but powerful. It gives the Scrum Team a shared understanding through which to evaluate every idea. It also helps the Product Owner make clear value-based decisions.

3. Prototype to Learn, Not to Impress

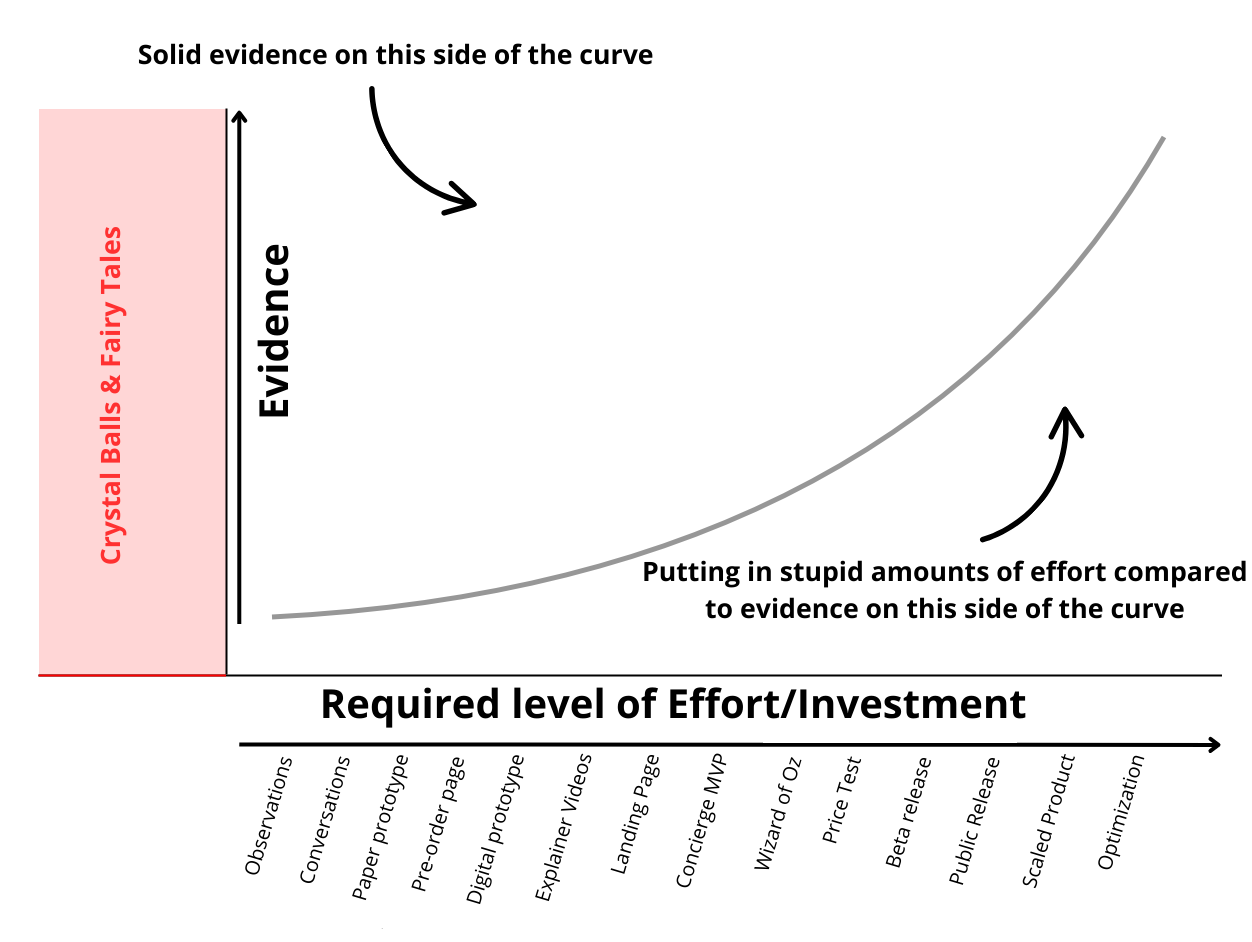

One of the most common mistakes is over-investing in an idea before testing it. Prototypes are disposable experiments. They’re sketches, mockups, or fake landing pages designed to answer one question: does this spark hold up in the real world?

Scrum’s empirical process, inspect and adapt, fits perfectly here. Each Sprint can test a different aspect of the spark. Sometimes, the outcome is “this isn’t worth building.” Often perceived as failure, this is actually a great learning as it saves further futile investments. The point is to gather evidence before investing.

Sparks in Action: The Pandemic Example

Think back to early 2020. For years, most organizations said remote work wasn’t possible: “We don’t have the infrastructure.” “It’ll take months.” “It can’t be done.”

Then the first lockdown hit. Within a week, millions of people were working from home. The spark of necessity triggered creativity. Zoom, Miro, and other collaboration tools exploded. Teams adapted almost overnight.

Scrum Teams lived this reality too. Those with strong problem-solving habits thrived. Those stuck in heavy upfront planning struggled. The spark wasn’t a grand strategy, but the urgent need to keep delivering value in a radically changed environment.

What Sparks Mean for Product Leaders

If you’re a Product Owner, you don’t need to generate every spark yourself. But you do need to notice them. That means staying curious, listening deeply to users, and resisting the urge to jump to solutions.

Think about questions like:

Where are people frustrated?

What are they trying to achieve that current solutions don’t allow?

What small prototypes could we run to test whether this spark matters?

Great products rarely begin with, “We set out to build X.” More often, they begin with, “We noticed Y, and decided to explore it.”

A Call to Curiosity

The Spark of Life is about being present and mindful enough to notice tensions in the world, and disciplined enough to test whether they’re worth solving. Especially in a world where we are constantly being distracted, it's hard to sit down, relax, and create the required mental space to see this potential.

Scrum gives us the perfect framework for this. Each Sprint is an opportunity to turn sparks into insights, and insights into value. Not every spark will become a product, but every product began with one.

So next time you feel frustration in your work, or see a gap in the market, don’t brush it off. Write it down. Share it with your team. Unlock that "What if...?" with the people around you.

Because that moment of tension could be the spark that lights your product’s future.