Yes, we have a product and…

Figuring out what your product is the critical step in a Scrum adoption. Why? Because it defines:

- who will be the Product Owner,

- the content of the Product Backlog,

- the composition of the teams.

The way you define your product — broad or narrow — changes everything:

- how large the area of optimization can be,

- level of business impact to expect,

- amount of organizational changes,

- how close you get to the customer.

A narrow product definition often leads to local optimizations: teams improve a small part of an organization, but not the whole business model.

On the other hand, too broad definitions could be impractical: the Product Vision gets blurry and the Product Backlog contains “everything”

A broader definition gives both adaptability and speed: teams become more cross-functional (feature teams), they can pick work from different product areas, and react faster to shifting priorities.

At the same time, narrow products reduce cognitive load and increase productivity through specialization.

There is no universal advice on how broad a product should be. It depends on what organizational capabilities you want to build and what strategic focus you set as a priority.

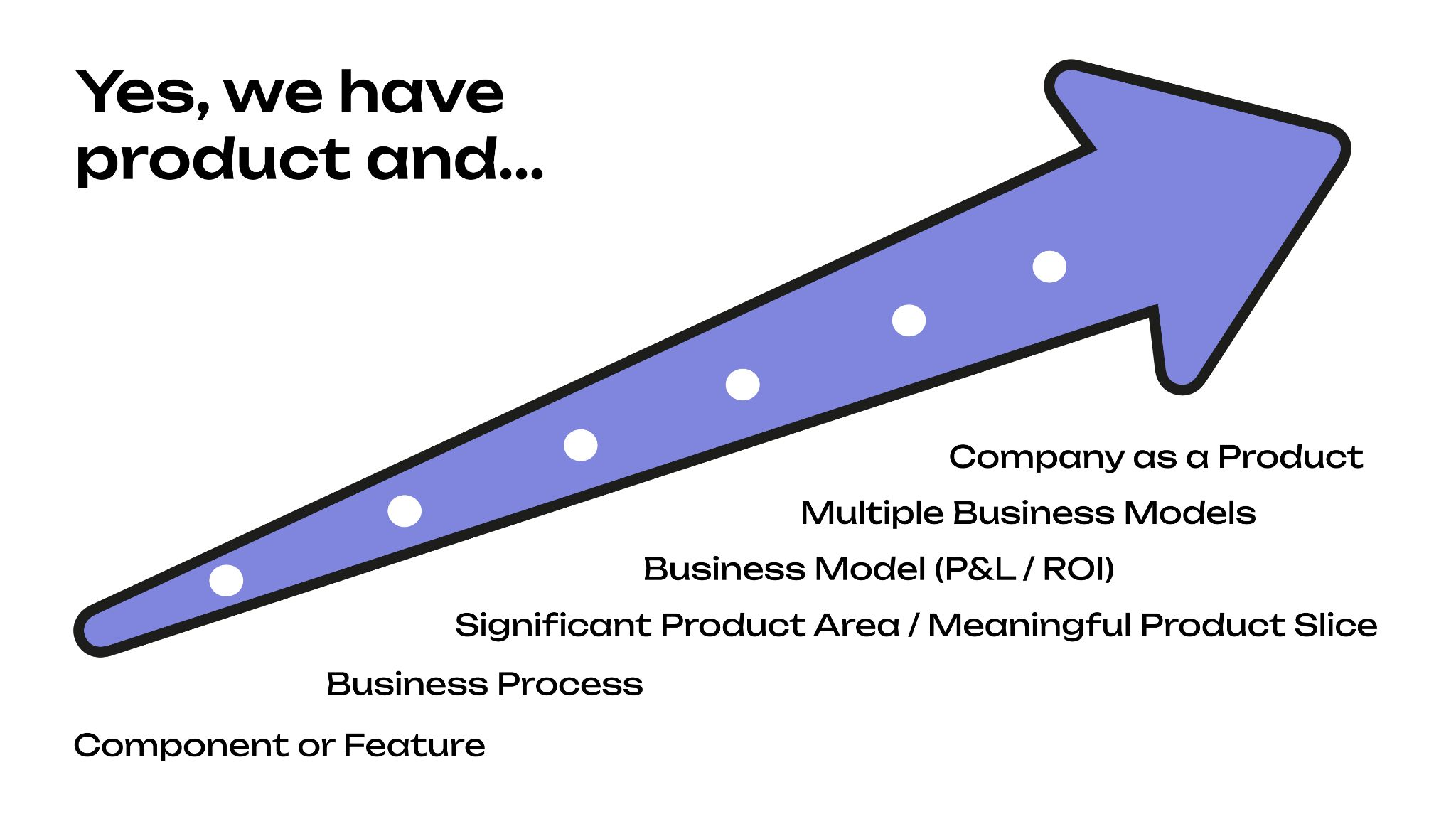

Let’s look at different product definitions — from the narrowest to the broadest — that I have seen in practice.

Product Gradients

Product Gradients

Component or function.

Scrum is used at the level of a single architectural component / function or a team building one widget. Examples: a platform team, a CRM BnB team, a push notifications team, analyst teams, testing team, and so on. This is the narrowest possible product definition — and most likely not the place you want to be.

Business process. A broader definition that includes several components. Speeding up individual business processes can sometimes bring a strong economic effect. Example: at Alfa-Bank we built teams around the internal account opening process, and they showed a clear increase in speed. This proved Scrum’s effectiveness and allowed us to continue the transformation. With an operations-centered focus, it is perfectly fine to build teams around processes (logistics, pricing, and so on). This is often where you can get solid business results.

Significant part of a BM (business model). Teams are built around an important part of the business model: a sales channel, a part of the customer journey (CJM), a separate segment, a funnel, or large interfaces. Examples: customer onboarding as part of the CJM, or a driver app in a taxi business (just one part of the model, since there is also the customer-facing side). This definition is broader than a process, but it still does not cover the whole business model.

Business model (P&L / ROI). This is where super-system optimization begins, and where Scrum works like real magic for your organization. The product definition now covers the entire business model. The Product Owner becomes an entrepreneur. A product group might include not only product development but also supporting functions: sales, marketing, risks, compliance. Examples of such products: television, car loans, payments and transfers.

Several business models. The Product Owner takes responsibility for several business models at once, and the organization gains even more adaptability. Example: debit cards, payments and transfers, and deposits are combined into a single product — the transaction business. Another example: car loans, cash services, and POS are combined into one product — lending.

The whole company as a product. This is the highest level of organizational adaptability. Imagine you are a bank and see the entire business — retail and corporate — as one single product. Inside this “product,” the retail area already includes several business models: lending, transaction business, and others. Such a definition is quite rare, but it opens the possibility to think of the whole organization as a product, fully built around the customer and value.

Conclusion

Defining the product is a critical decision in Scrum adoption. Its scope affects everything: from team structure and the role of the Product Owner to the scale of optimization and the level of customer-centricity in the organization.

Narrow definitions give focus and specialization, but risk local optimization. Broad definitions bring adaptability, cross-functionality and speed, and closeness to the customer, but also the risk of a blurry vision and an overloaded Product Backlog.

There is no universal answer. Each organization must find its own balance, based on its strategic focus and the capabilities it wants to build. Thus you decide whether Scrum stays a local practice in one department or becomes a systemic lever for transforming the whole business.