Many product teams think of pricing as a late-stage decision, if the pricing is in their control at all. “We’ll figure it out before launch,” or worse, “Let’s copy what the competition does.” But pricing isn’t a detail to tack on at the end. It’s one of the most powerful product levers we have, and one of the most under-explored.

In The Anatomy of a Product or TAP (release scheduled for December 1st), we describe pricing as a hypothesis. This, too, is an assumption about value, willingness-to-pay, and customer behavior. And like any assumption, it should be tested empirically.

Scrum gives us the perfect framework to do exactly that.

The TAP Pricing Formula

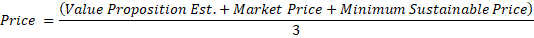

Pricing can feel like a guessing game, but there’s structure behind it. TAP uses a simple formula to frame the conversation:

- Value Proposition Estimate (VPE): What do we estimate our users are willing to pay? This may be based on experiments, research, interviews, or other sources.

- Market Price (MP): Are there any competing products, and what are they charging?

- Minimum Sustainable Price (MSP): What is the lowest price we, as a producer, need to stay in business? This is affected by the number of users we're expecting to stay in business.

Change any one of these variables, and your pricing hypothesis shifts. Note that this is a very simplified version of pricing tactics, and they should not be underestimated, but we found that this is a conversation starter that can and should be refined and improved as you learn more.

Why Pricing Matters Early

Scrum is about maximizing value, not output. But how can we maximize value if we don’t know what users are willing to exchange for it? Pricing experiments help us uncover that. A backlog full of features doesn’t mean much if the product ends up priced outside of what customers find reasonable. Similarly, pricing too low can undervalue your product, hurt margins, and slow growth. The earlier we bring pricing into discovery, the faster we learn what truly matters to customers.

Running Pricing Experiments

So, how can Scrum Teams test pricing in practice? Here are three simple approaches:

1. Fake Doors

Create a landing page with different pricing options. Let users “choose” a plan, even if the feature isn’t live yet. Track clicks, conversions, and drop-offs. This gives a strong signal of willingness-to-pay before you build.

2. A/B Pricing Tests

If you already have active users, test different price points with small cohorts. Measure not just conversion but also churn and engagement. Pricing is about lifetime value, not just initial purchase. Ask them for their opinion if you have the chance to.

3. Packaging Experiments

Sometimes the issue isn’t the price, but more about how the product is packaged. Bundle features differently, experiment with “good / better / best” tiers, or test add-ons versus all-inclusive pricing.

Each Sprint, a Scrum Team can frame a pricing experiment as a Product Goal: “Learn which of these two pricing options generates higher sign-up and retention rates.” Personally, I think learning objectives as a Sprint Goal are the least common of all Sprint Goals I have seen, and I would LOVE to see more of them.

The Role of the Product Owner

Although decided by other people, the Product Owner plays a critical role here:

Framing Pricing as Value: Not “What should we charge?” but “What is the value exchange?”

Prioritizing Pricing Experiments: Including them in the backlog alongside features and improvements.

Synthesizing Evidence: Using insights from experiments to guide go-to-market decisions.

By treating pricing hypotheses like backlog items, Product Owners ensure the Scrum Team validates assumptions that directly impact revenue and sustainability.

Image by the amazing Olina Glindevi

Common Pitfalls

It’s tempting to treat pricing as a one-time choice. But markets evolve, competitors adjust, and customer perceptions shift. A healthy product adapts its pricing over time.

Three common traps to avoid:

Copycat Pricing: Assuming your competitor’s pricing fits your context. It rarely does. Equally, IF you go for the same price, how does your product differ from the competitors to justify the same price?

One-and-Done Pricing: Setting a price at launch and never revisiting it.

Feature-Justification Pricing: Basing prices only on how many features are built, not on the problem solved.

Scrum’s iterative nature helps us avoid these pitfalls. Pricing becomes part of continuous discovery, and is a perfect discussion point during Sprint Reviews. If other people, like sales folks, decide on the price, invite them to your Sprint Reviews too. Then it turns into a collaborative effort, rather than a us-versus-them show.

A SaaS startup I worked with assumed their product should be priced at $29/month, matching a competitor. Instead of locking it in, they ran small tests. To their surprise, the strongest conversion and retention came at $49/month; users associated the higher price with higher reliability. Had they copied the market, they would have left significant value on the table. By treating pricing as a hypothesis, they found the sweet spot empirically.

Final Thought

Pricing is too important to be left to guesswork or to the finance department alone. It’s a core part of product value, and Scrum gives us the perfect mechanism to explore it iteratively. I know this is a radical statement for many organizations. Still, the job of a Product Owner is to maximize value, and this is a big (and mostly neglected) aspect of that maximization.

Remember:

Pricing is a hypothesis, not a fact.

Experiments are cheap; mispricing is expensive.

Value perception, willingness-to-pay, and alternatives define your formula.

The backlog isn’t just for features. Repeat after me. The backlog is not just for features. It’s for everything that drives value, including pricing.

So, in your next Sprint Planning, think about this question: What pricing assumption can we test this Sprint? Or even: "Based on what did our current price form?"

Because the right price, validated by evidence, can be the difference between a product that survives and one that thrives.